A young European explores Chinese dynamism and calls for critical reflection on Sino-European relations.

A foreigner uses mobile payment to purchase cultural and creative products at the Shouxian Museum in Huainan, Anhui, September 5, 2025.

This is not the first time that I have set foot on Chinese soil. My first trip was in 2018, on a family trip to reconnect with our roots. At that time, absorbed in my studies, I knew almost nothing about the history and modern landscape of China.

After spending a week in Hangzhou (Zhejiang) and Beijing as part of the China-Europe Youth Dialogue 2025, impressions and discoveries are pouring in. While it is difficult to single out one as the most striking, I undoubtedly remember the omnipresence of digitalization.

Between tradition and modernity

I had already heard anecdotes from relatives who had emigrated to China. They explained to me that in Europe, paying by card was modern and cash was out of fashion, while in China, paying by phone was the norm and paying by card seemed obsolete. Seeing for myself the simplicity with which a foreigner can now link their bank card to an application and dive into this world of mobile payment was a real revelation. I saw my European colleagues marvel at this disconcerting convenience.

In Hangzhou, beyond the transactions, I perceived a striking open-mindedness. The locals did not hesitate to come towards us to take photos, sharing these moments on social networks. To me, this speaks to the Chinese desire to interact directly with the world: while the language barrier remains, technology acts as a powerful bridge, helping to bridge this gap.

Furthermore, the visually distinctive mix of contemporary and traditional architectural elements sums up, for me, China’s current approach: opening up and modernizing while remaining deeply rooted in its interests and culture.

Participants of the 5th Thematic Training Session of European Young Leaders visit the East Lake High-Tech Development Zone of Wuhan (Hubei), also known as “Optics Valley”.

Complex China-Europe relations

The European Union (EU) defines China as “a systemic partner, competitor and rival”. This classification, if it is intended to be intuitive, deserves critical reflection, especially following my stay in China. I am convinced that certain common perceptions of China in Europe remain deeply influenced by media narratives, which distort the understanding of the realities of this country.

After 1978, China’s opening up was interpreted by our education system and media as simple “market reform”, fueling the thesis that China would eventually adopt the Western political and economic model. With hindsight, this interpretation clearly turns out to be too simplistic. Throughout its opening-up, China has maintained control of its own development path. Some Western observers, for a time, made the mistake of confining China to the role of “factory of the world” – a blatant underestimate. Today, the country is charting an economic path distinct from that of many developing countries and that followed by postwar Europe.

At the same time, I observed a worrying trend. Eager to maintain its global leadership, the United States sometimes adopts policies that put pressure on its European allies. However, faced with this, certain European political decision-makers seem stuck in the desire to preserve the traditional transatlantic alliance framework. Perhaps they see it as the most prudent choice, a way to maintain their influence and position. However, it is worth asking whether this choice corresponds to the long-term interests of the European population.

When the priorities of policy makers move away from the well-being of citizens, social distrust increases. This disconnect could well be one of the major reasons for the rise of populism in Europe in recent years.

The label “systemic rival” reflects above all Washington’s geostrategic calculations. By adopting it without nuance, Europe has perhaps not sufficiently measured the implications of this posture for its strategic autonomy and for the defense of its own sovereign interests.

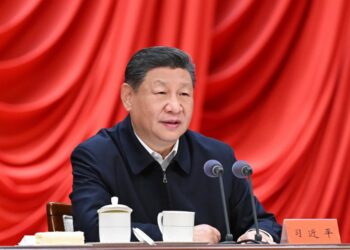

Hugo Martin speaks during the China-Europe Youth Dialogue 2025

The role of the younger generation

It is in this context that the point of view of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEEC) takes on its full meaning. As a region striving for economic prosperity, many CEE countries have every interest in intensifying their trade dynamics with China. If the development of infrastructure such as the Budapest-Belgrade-Skopje-Athens railway succeeds in boosting the regional economy, it would prove to the rest of Europe that cooperation with China can be truly win-win. This concrete success could then open up new perspectives for the EU’s foreign and trade policy.

This naturally brings me to the role of our generation. There is, in my opinion, a major misconception: young Europeans and Chinese often tend to believe that the challenges we face are radically different. In reality, we face the same fundamental problems: feeding ourselves, housing, having a meaningful job, starting a family and providing education. Platforms like the China-Europe Youth Dialogue constitute an essential form of parallel diplomacy, allowing young people from Europe and China to get to know each other better.

In my opinion, our current responsibilities revolve around three pillars. The first is economic advocacy, which involves committing to more open and balanced trade policies in our own countries. The second is experience sharing, that is, spreading our observations, thoughts and understanding of China through stories, conversations, images and videos. Only through sincere dialogue will more people see the complex realities of China-EU relations and their immense potential. Finally, the third pillar is lifelong learning, which involves mastering the Chinese language, keeping informed of China’s socio-economic development and fully understanding the challenges of interaction between Europe and China.

In today’s world, ideological grand narratives can sometimes drown out factual logic. But, as American educator John Erskine said, we have a “moral obligation to be intelligent.” It is this intelligence that will allow us to overcome fears and prejudices to move towards a truly shared future.

*HUGO MARTIN is a guest researcher at the Danube Institute.